By Arpad Okay. When The Electric Sublime #1 hit stands last month, it set our synapses to firing. Here’s a wild concept: When the world’s most famous art pieces appear to have changed — from the inside — it’s up to the director of the Bureau of Artistic Integrity and a mental patient named Arthur Brut to tap into a bent reality called the Electric Sublime to get to the bottom of things. That’s either a cleverly posited commentary on arts appreciation or a damning indictment. Let’s all just take a moment and attempt to wrap our heads around that.

If you’ve ever found yourself tremulously moved by a piece of art, The Electric Sublime is here to throw you into the proverbial volcano. It approaches the art world, not so much to navigate it, but to forge new paths through it by a sheer force of will. It’s here to peel away all pretense. At least, that appears to be the intention of series writer W. Maxwell Prince. It’s hard to say.

“I’ll say that I’ve always found art to be a mode of communication that one turns to when other modes are failing,” the writer told DoomRocket this past month.”[…] the DNA of art and madness are intertwined and complement each other in ways that are hard to talk about.”

Like we said. Hard to say.

Barely two issues in, the latest from IDW Publishing has acquitted itself marvelously as an exciting new project, sitting pretty with a 9.4 score from comics review aggregate website ComicBookRoundup.com. Timed with this week’s release of the book’s second issue, DoomRocket contributing writer Arpad Okay has shared his exchange of ideas with Mr. Prince about The Electric Sublime, the noble pursuit of comprehending the abstract, and a Bruce Wayne who takes time out of his day to paint.

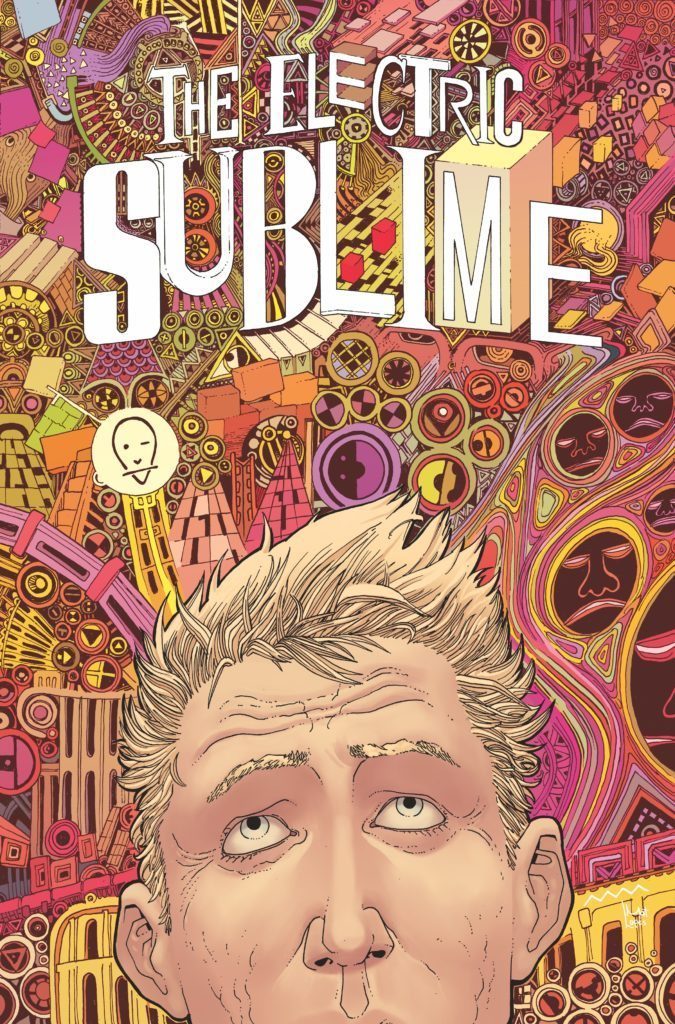

Cover to ‘The Electirc Sublime’ #1, courtesy of IDW Publishing. Art by Martín Morazzo.

1. One of the things that first struck me about ‘Electric Sublime’ was the power colors have over the mood. It feels like there’s a shift in palette for every change of scene, as though the emotional moments are dictating the color choices. Do the scripts specifically call for things like this, or are choices like that left to the art team?

W. Maxwell Prince: There are a few specific color cues in the scripts, e.g., the paint splatter on the stark white suits of The Correction, but most of the palette shifts are attributable to our colorist Mat Lopes’ brilliant eye. I don’t think I’ve ever seen someone do such good work over Martín’s lines.

2. At the start, I was under the impression that reality was warping. But after the odd implications concerning Art Brut’s past work, I’m not so sure the reality of ‘Electric Sublime’ is our reality after all. How do you determine how much of the setting is real and how much is fantastic — when do you feel free to break the rules, where do you stop yourself?

WMP: Much like real life, the borders of The Electric Sublime are porous: the fantastic and the real overlap and eventually become indistinguishable. For my part, I spend a large chunk of my weeks marveling at amazing things that are, in fact, happening right here in this humdrum little world of ours.

3. Why Manny? The desktop wooden mannequin is an absolute ironclad staple of foundation courses everywhere, to be sure. But what a delightful pull, a shockingly on-point and specific choice for a spirit guide. Is it time the artists’ model got their due?

WMP: It is! I could think of no better spirit animal for Arthur than a walking, talking wooden mannequin. But what started as a merely clever idea — giving life, à la Pygmalion, to the model — eventually turned into something I hadn’t anticipated; writing Manny’s dialogue is an exercise in pure, unadulterated joy. He’s a hunk of inanimate wood, and yet I think he’s maybe the runaway star of the book.

4. Speaking of paying dues, the issue opens on the Louvre. Give me your museum bucket list. Where do you go to go see the good stuff; where haven’t you been that’s killing you? Tell me about the museums that everyone should make an effort to visit.

WMP: Well, I live in New York, which has some of the best museums in the world. The Met, MoMA, The BK Museum, the American Folk Art Museum. For my money, the Prado is probably the most fantastic gallery for the casual art observer. It’s nestled into a really delightful part of Madrid, and houses, I think, the largest Goya collection of any museo in the world.

5. Margot Breslin, Director of the Bureau of Artistic Integrity, is far and away my favorite character in the book. As a POC and as a lady, she shakes off the grip the predominantly (white) boy’s club has had on the fine art world since forever. Where did Breslin come from? I would love to know if it’s a political choice or a mere coincidence of good writing that makes her break the mold.

WMP: The boring answer is: the way you see her in the book is the way she appeared in my head when dreaming up The Electric Sublime. The socio-political implications of her character aren’t lost on me — she’s a lesbian, to boot — but she’s merely portrayed with fidelity to what I wrote in my notebook when I started scribbling for this project.

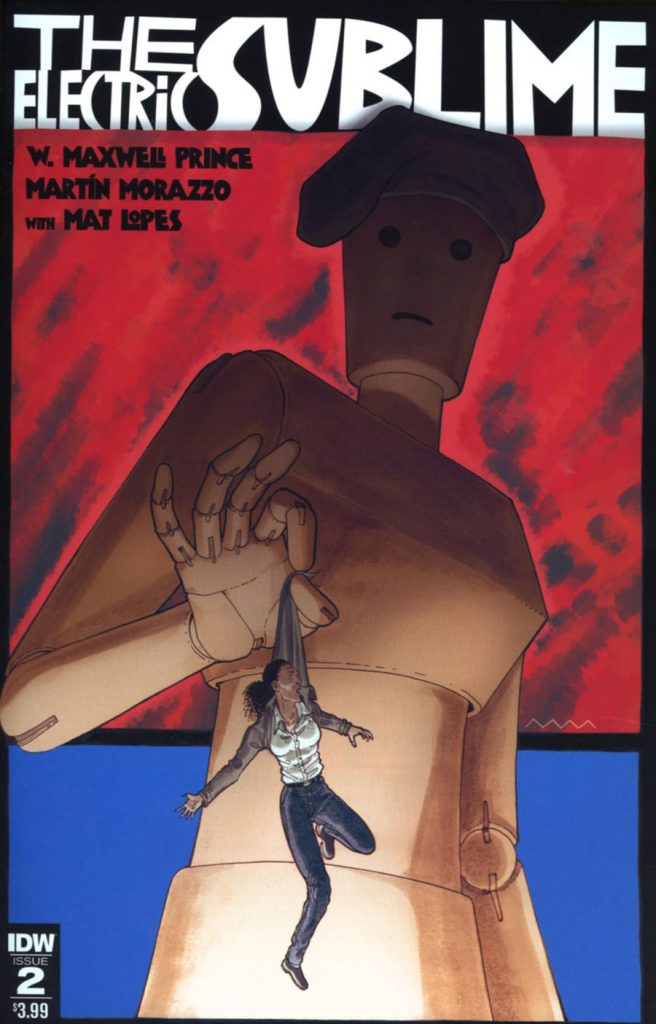

Cover to ‘The Electric Sublime’ #2. Art by Martín Morazzo.

6. Why choose artists as the group to become killers and supervillains? Tell me your thoughts on the relationship between a creator’s sensitivity and their capacity for extreme behavior. It’s a wonder to me that more superheroes and villains don’t have hobbies in the arts. I could see Batman painting. Peter Parker is a photographer.

WMP: The historical ties between art and mental illness are well documented and can be explained by folks much smarter than me. But I’ll say that I’ve always found art to be a mode of communication that one turns to when other modes are failing. Art has its trunk cables tied right into our emotions: when you have a bad day, maybe you’ll listen to an album you love, or watch a show that brings you joy; some people walk around museums to clear their heads. Then there’s the salutary effects of creating art: people paint to calm down, or type furiously into their laptops to spill their thoughts. The DNA of art and madness are intertwined and complement each other in ways that are hard to talk about. To me, an artist is the perfect candidate for a super villain or a murderer — I’m reminded of what an aesthete Hannibal Lecter was, or that unforgettable scene in Tim Burton’s Batman when Nicholson’s Joker defaces a bunch of paintings.

I’d love to see more mainstream superheroes contend with art. I’d pay good money for a Spider-Man story about Peter Parker trying to take better pictures, or a Batman arc about gothic painting. I think Grant Morrison scratched the surface there, if I’m remembering correctly.

7. ‘The Electric Sublime’ is only starting out, but so far it seems to have the strongest ties to the Classics. I read the afterword in issue #1, I groked the Warhol; the definition of art here is refreshingly broad. My question is, what won’t fit? Is there a place in the other world of the Sublime for Haring’s graffiti dog, or McCarthy’s Christmas Tree? Is there a shabby suburb for internet fan art, a farm to buy handmade craft goods?

WMP: The thesis of The Electric Sublime is that every piece of art is living and has a world inside it. It’s all fair game, and I sincerely hope I get to write Arthur jumping into some graffiti, or walking around a song.

8. I think that being iconic can sometimes rob art of its power. Something like “The Starry Night” is still immensely humbling to see in person, but most folks know it as a shower curtain, a fridge magnet, the inside of an umbrella. What do you think can be done to make sure that fine art still moves people?

WMP: I think we have to humble people in the way you suggest: get them to museums to see the real thing. My hope is that someone with a Starry Night shower curtain or mousepad — do they still make mousepads? — would feel, at the gut level, the stark difference between those kitschy little commodities and the unmitigated splendor of standing before a giant piece of genius that someone communicated straight from their fingertips.

9. This kind of plays off of a question from earlier, but I can’t get the image of the sculptors who bronzed their living children out of my head, so here we go. To take an idea and give it form is the essence of art and it is an ability that comes pretty much exclusively with self-awareness. But with it, in this book at least, comes the capacity to murder. Do you think that madness and cruelty are a part of ourselves, or is the drive to destroy something that comes from outside of us?

WMP: Golly, that’s a good question. I don’t know that I can speak for other people. But I can say what drives to create and destroy occupy a fairly equal amount of space within me. I think that might come from the tacit contract you sign when trying to make something: no matter what you “create,” the final product is a betrayal of your hopes for it. It’s just never as good as the beautiful, perfect, salable idea you had in your head. So the urge to destroy, or cease, starts to rear its head, sink its claws in. Your fidelity to perfection forces you to consider: should I just nix this thing, since it’s not what I’d hoped? We can all envision the tortured artist or writer ripping up her output in some messy studio, cursing the muses or whatever. And in a perverse way, that idea can apply to children—progeny can disappoint you much in the way that creative output can. But I wouldn’t suggest bronzing your kids.

The interesting project is learning to live with what you do/make, which I think requires a certain stifling of that urge to destroy.

10. You love fine art. You love comics. That’s why ‘The Electric Sublime’ exists. Give me some above and beyond comic book recommendations. When some lost spirit says comics aren’t art, what do you bring up to prove comics can achieve the heights of Botticelli or Bach?

WMP: I’m reading Sandman: Endless Nights right now (I do so once a year), and it never ceases to just blow my hair right back. It’s so, so good.

But I’d also like to posit that any comic, new or old, is actually just the product of the same artistic choice that Botticelli made before Venus: to make something. There’s plenty of scholarship about the differences between high and low art, but the truth of the matter is that both (in most cases) derive from the same artistic impulse: to use your head and your hands to create matter from air. I think we can all use to be a little more generous in our appraisals of “art.”; it’s a noble pursuit to try your hand at making anything.

‘The Electric Sublime’ #2 is in stores now.

Before: 10 THINGS CONCERNING Zander Cannon And The Second Season of ‘KAIJUMAX’