By Arpad Okay. Carver: A Paris Story is the kind of comic you would find in another work of fiction, something Wilson Fisk or Lou Ford might have grown up reading. It’s too good to be real. Vintage war comics are violent by design, sure, but the real life classics have a disappointing safety to them. Everything is justified by casting both sides of the conflict clearly as heroes and villains. Well, Chris Hunt is serious about the real cost of violence, not war but what comes after. Carver is not The Battle Hymn of the Republic, it’s The Ballad of Mack the Knife as sung by Iggy Pop. It’s Stack-O-Lee Blues, the original version where Stack shoots Billy, goes to prison and is tormented in his cell by demons for the rest of his life.

Carver is the rock n roll progeny of Weird War. The beats of the classics are there — witty repartee, reunited lovers, and dark memories of active service. But instead of feeling archaic, Carver transitions smoothly from the intimate to the macabre; all facets of the soldier’s tale have been streamlined into a story that is modern and bold, amoral and personal. Hunt writes with the harsh machismo that permeated the times, the old version of Stacker Lee before his act got cleaned up for American Bandstand. War is ugly. That is what the vintage comics omit. But Carver leaves nothing out. It is pulpy and dreamily noir but there is a neo-realism seriousness that gives the comic as a whole serious bite. Carver resembles Orson Welles and The Third Man more than the nostalgic, Saving Private Ryan safety of war comics from the past.

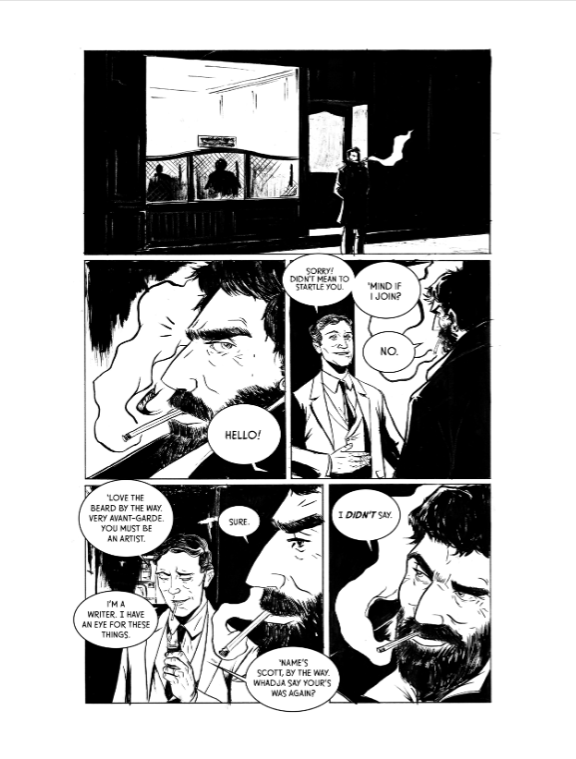

courtesy of Z2 Comics.

Hunt’s artwork is as distinctly different from the expected as his storytelling. All-American Men of War and Marines Attack and War and Attack were all fairly indistinguishable from each other, almost industrial in their production. Carver is in no way just another comic about war to throw onto that pile. Chris Hunt has a patient pen fit for illustrating Collier’s or The Saturday Evening Post. His work in monochrome evokes the postwar setting of the book itself. There is an almost academic pleasure in reading Carver, the art is good, but it is also thoroughly satisfying to see someone with talent hard at work on their craft and doing well. There is a reverence for the look of the era but always done in Hunt’s distinct personal style. It takes real control to do right and to see it done perfectly is a rare thing indeed. I feel the influence of the sparse jazz baby lines of artist Tim Sale, but Hunt is such a whole package guy, the man he truly deserves comparison to is writer/artist/publisher/savant Eddie Campbell.

Carver is what you get when a creator’s experience has a youthful spring in its step. A slow burn of mounting tension and sudden payoff. Delaying gratification the way Hunt does is risky; you have to have both maturity and confidence to really pull it off, and he does. My favorite aspect of the issue is it contains a reverie. Not merely a dream or a flashback, but a message from the oracle that is an appropriate throwback for a postwar romance story like Francis Carver’s. His surreal troubles don’t end with the fantasy sequence and things escalate to a whirlwind conclusion. Stacker Lee is back, larger than life, and Hunt gives this cartoon real menace. He’s turned the Phantom Blot into Fantomas.

What I see in Carver is the promise of strong storytelling. Hunt understands what works and does it in his story, his familiarity with Carver’s world gives him the confidence to use extreme, disturbing circumstances to punch up the tension without violating the overall attention given by the reader. From gunfire to hand holding, he never takes us out of the moment.

Z2 Comics/$3.99

Written and illustrated by Chris Hunt.

Letters by Chris Hunt.

6 out of 10