THIS REVIEW OF ‘ORPHAN AGE’ #1 CONTAINS MINOR SPOILERS.

by Clyde Hall. If every comic, novel, and movie touting an It’s the End of the World theme registered at one decibel, combined they could peg sufficient volume for an R.E.M. stadium tour. Cacophony enough that any new entrant into the arena should establish a disparate angle and uniqueness to best be heard. To do otherwise adds only to white noise. AfterShock Comics now treads an apocalyptic path worn smooth by zombie infestations and global epidemics with this week’s Orphan Age #1.

Twenty years before the main storyline, modern civilization plugged along much like ours. Technology made life grand, or at least more convenient. People led soft lives of comfort and plenty. Survivors were just contestants on a gameshow. Until a day came when all adults simply fell dead, leaving behind a world inhabited only by children.

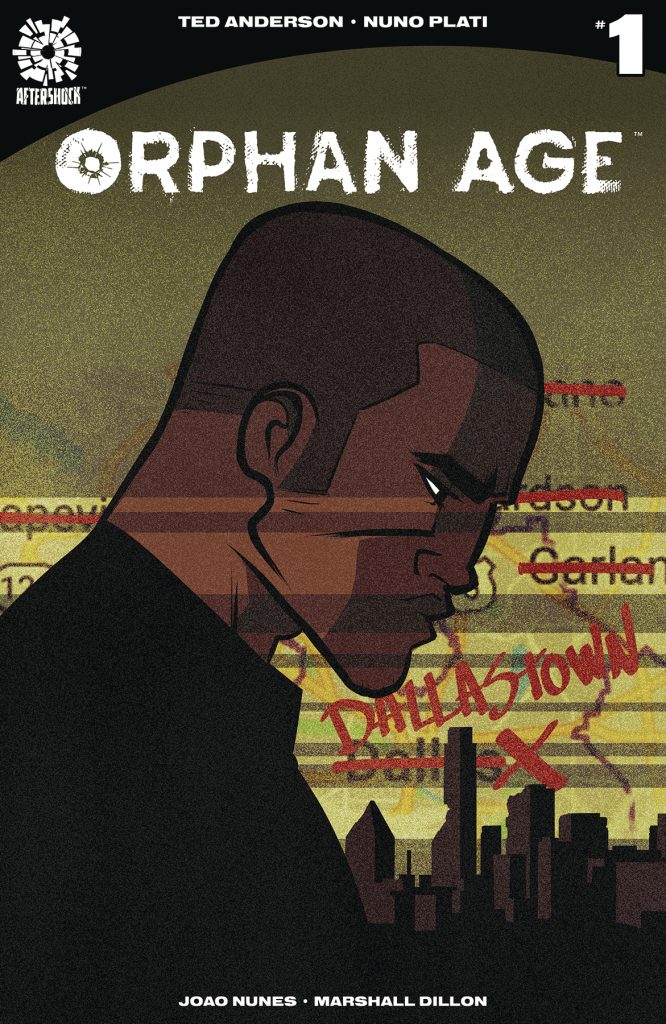

In the survivor society that’s risen over two succeeding decades, those kids have become adults and had children themselves. Human civilization, once more propelled by horse-power and illuminated by candle and lamplight, has found a way to endure. Without apparently discovering reasons for the adult extinction, the survivors have established farming hamlets and towns reminiscent of America’s late 19th Century.

Mayor Brian runs one such small farming community, a close-knit collective that has book-reading clubs, limited medical resources, and basic schools. Brian’s pre-pubescent daughter, Princess, helps with the teaching. A wounded stranger wanders into their village warning of an armed New Church force likely headed their direction. This leads Princess, Daniel the stranger, and a travelling bard named Willa on a panic-fueled flight to a place called Albany.

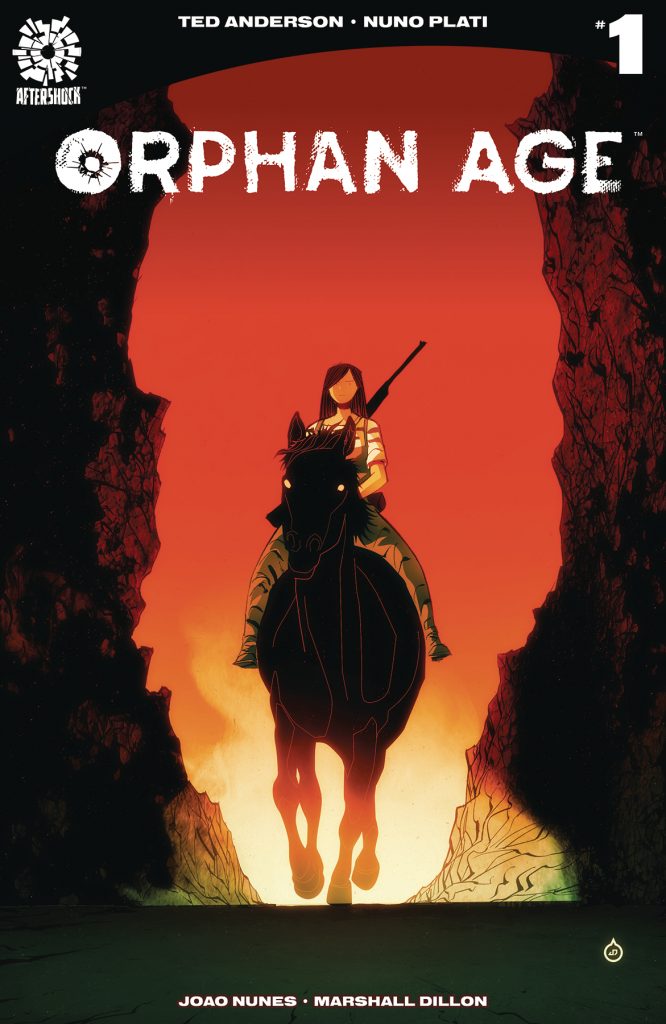

Writer Ted Anderson predominantly establishes these three protagonists along with the Mayor. Princess is the youngest, a kid watching the stable existence she’s known change forever. Daniel is a serious survivor, one who has escaped massacres and who delivers pistol headshots from horseback at full gallop. Willa is soulful and quiet, a loner who remains mobile and shares her songs in exchange for food and a cot. It’s how she copes with a past still too painful to share.

The concept of an instantly de-adulted world holds much promise. It could be a global Lord of the Flies, or a tale of the oldest youths banding together to protect the youngest. Taken purely as a horror spin on childhood phobias of being lost and abandoned, it has legs. The psychology of a world populated only by children and how that evolves into the story’s setting is an obvious vein to tap. Anderson’s given it more of a nudge with the first issue. There’s mention of guilt and nightmares during a town Sharing session, but scant memorable exploration. Groundwork is established for future issues to delve, but a bold, emotional piton isn’t driven home. The initial idea still has ample-if-dormant capacities to capture our attention. Unveiling them will require patience.

The villainy of the New Church is also largely non-specific. History is rife with zealotry leading to slaughter, so that’s no stretch. But as presented, the New Church is a generic movement apart from a Second Flood ideology. Their ‘join us or die’ philosophy is established, but it’s featureless and unlike the theocracy of The Handmaid’s Tale, which announces some part of itself from title forward, The New Church here requires additional detailing as the narrative continues.

Nuno Plati’s art has an unfinished appearance and appeal; the look he fashions fits a civilization where, if structures are standing and useable as shelter, that’s good enough. There are beautiful panels almost blueprinting some constructions. These make excellent portals into the nature of the survivors’ lives, the kinds of places they’d build or convert as homes.

It’s a wan world of childhoods ended too soon as colored by João Lemos. Life requires manual labor and focus, not frills, and he establishes that ably enough. His scenes after dark, characters illuminated by open flame, are exceptionally atmospheric and played for impact. On lettering, Marshall Dillon gets in nice variations between song, normal-speak, and conversation snippets overheard in crowded settings. Like Plati’s art, the style is basic, functional, and reflective of a society where such qualities are favored.

Andersen and his crew have the potential to make their voices heard in the R.E.M. blare of a new human age propagated by mass extinction. Their concept of a child’s world should haunt the reader as much as the music video of It’s the End of the World. Therein, a boy and his dog moodily sort plastic discards of a fallen civilization while the youth’s shadow slowly detaches from its caster like a creepy Peter Pan homage. This premiere issue carries little of that undercurrent or impact. Orphan Age may realize such opportunities before all is said and done, but it’s off to a measured, delayed start.

AfterShock Comics / $3.99

Written by Ted Anderson.

Art by Nuno Plati.

Colors by João Lemos.

Letters by Marshall Dillon.

6.5 out of 10

Check out Juan Doe’s variant cover to ‘Orphan Age’ #1, courtesy of AfterShock Comics!