By Jarrod Jones. This is RETROGRADING, where sometimes it’s good to do what you’re supposed to do when you’re supposed to do it.

THE FILM: Frances Ha

THE TIME: 2012, two years after Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach first took a chance on angsty romance with Greenberg.

RECOLLECTIONS: There is nothing incredibly arresting about life during your late twenties. You’re either done with college and working a job in your chosen field, treading water until new opportunities float around, or you’re still in college and will be until you’re satisfied or turn fifty, whichever comes first. Relationships are either deathly serious and prolonged, or so fleeting that sometimes you forget they ever happened. Bills are insurmountable, but there’s always enough cash for another round of drinks. You meet people that are into this, or do that, and you plan on meeting for things like brunch or an art show or drinks after work. It’s all just a mundane trial period, a gauntlet for maturity that can be even more damaging and awkward than high school ever was, a neurotic holding pattern for the actual adulthood that awaits you.

Yet there’s something about that period in your life that makes things seem so important, so paramount, that you forget that just so long as you’re alive, above water, and surrounded by friends, you can be happy. Such sequences of ephemeral youth are at the forefront of Frances Ha, Noah Baumbach’s 2012 comedy co-written by his Greenberg star Greta Gerwig, a film about the messiness of a shallow existence, not knowing where you’re going but wanting to be there so, so badly. Those with a modicum of patience for flaky people dizzy with uncertainty might lose patience with certain events that unfold here, but Gerwig and Baumbach have crafted a story about these people with such a ferocious confidence that only the most jaded and cynical could possibly hate it.

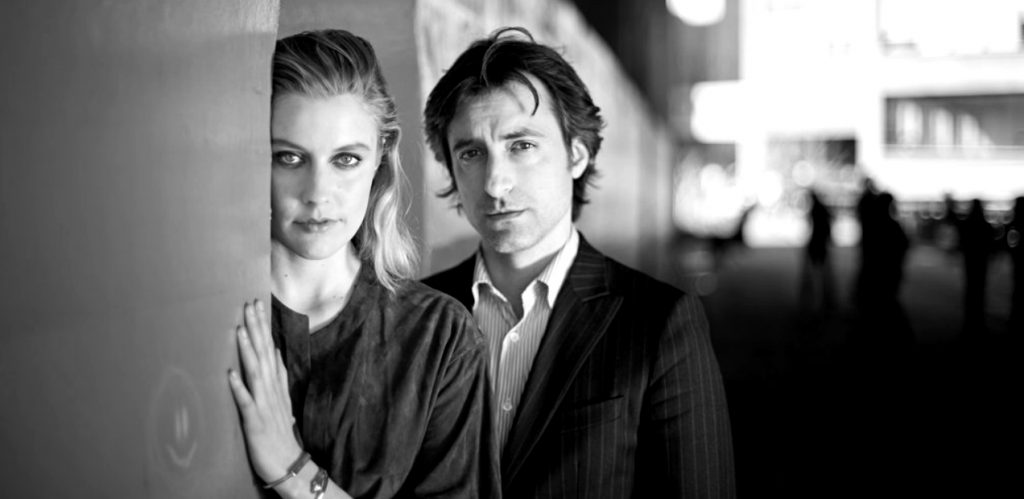

Frances (played by Gerwig) finds herself without a boyfriend, and soon minus one best friend. Sophie (Mickey Sumner) is getting serious with boring, safe boyfriend, Patch (Patrick Heusinger), and no matter how much Frances’ friendship with Sophie makes sense, no matter how often they tell each other how they will grow old together, there is only so much one person can do for the other, especially in the years where individual growth is so aggravatingly necessary. (“Tell me the story of us?” Frances requests. “Again?” Sophie shoots back.) Watching Frances navigate the emotional and verbal minefields for which she isn’t quite prepared makes her personal arc all the more compelling. Frances’ twenty-seventh year on Earth is very much a mess, albeit a fascinating, beautiful one.

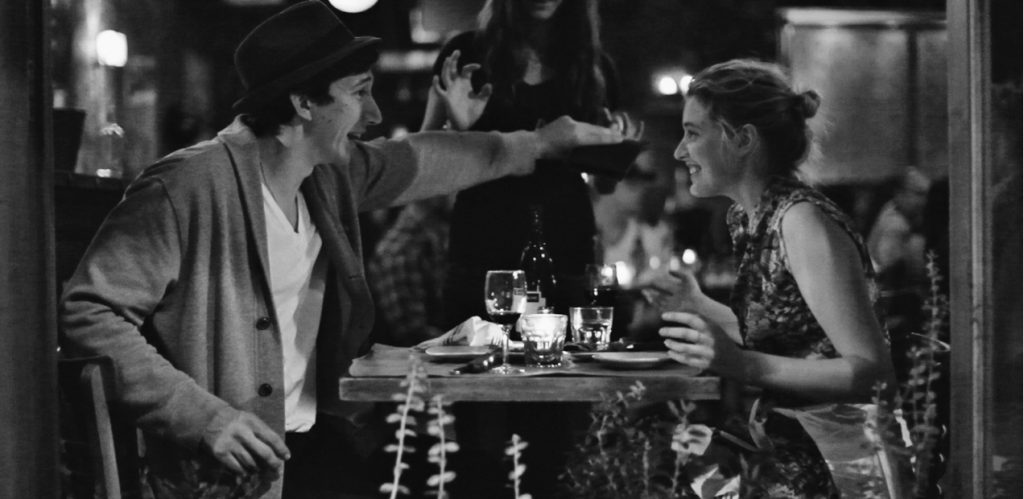

One of the more daunting sequences comes later in the film where Frances and her friend Sophie reconnect after some time apart. There is more than some mileage without each other, and growth — painful as it may have been — is obvious, projected plainly on the faces of these two people. With that growth comes a certain amount of wisdom, and it’s here that Frances Ha hits you square in the feels — their friendship, like so many relationships in our twenties, was just lightning in a bottle, two people at the same place in their lives at the same moment. As lovely as that sentiment is, a hard truth comes soon afterwards: moments are meant to be fleeting, that sometimes when someone tells you to take your socks off, all you’re left with is cold feet.

THE DIRECTOR: Director Noah Baumbach had been finessing his chinos-and-heartache motif over the years with films like Squid and the Whale and Greenberg (in-between stints of working with Wes Anderson on screenplays for The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and The Fantastic Mr. Fox). With Frances Ha, Baumbach had arrived as some kind of contemporary blend of Woody Allen and François Truffaut, though that’s largely due to his collaboration with actor/director/producer Greta Gerwig. The filmmaker’s patented misanthropy is offset just enough by her warmth, and Frances Ha is a better movie because of it.

Working together on a screenplay that left just enough room for improvisation, Gerwig and Baumbach captured a moment in New York City the same way Allen had in the late Seventies with Diane Lane in Annie Hall, and more acutely, Manhattan. (Baumbach’s stark cinematography, executed with precision by Sam Levy, punctuates the similarities to the latter.) The director frames the ideas of this film stridently in vistas of beautiful black and white, balancing a Godard-like exuberance with an Allen-like toxicity and caustic wit. Baumbach would go on to work again with Gerwig in the peculiar Mistress America, but Frances Ha remains their best collaboration to date.

THE CAST: The film is, in a sense, a love story, but the love portrayed on film isn’t conventional, or even saccharine; it’s the kind of love that relies on the intimacy of snuggling more than love-making. That love is potently depicted onscreen from the onset, between Greta Gerwig’s flighty Frances and Mickey Sumner’s sanguine Sophie. There is no sapphic subtext to the relationship; watching the two frolic in the urban junkpile known as Brooklyn is as romantic and lovely as anything else concerning the matters of the heart, until Frances decides to jilt her current boyfriend’s requests to move in together in order to accommodate Sophie’s needs as her best friend and roommate. When life gets in the way (as it does), things unravel quickly, and soon what was once uncomplicated and pure becomes anything but.

As Frances pinballs around her shattered world (shacking up with a couple of nimrod trust-fund artiste types played by Adam Driver and Michael Zegen), she passively aims towards rising above her well-earned Alternate status in a premiere New York dancing company. The real fuck about Frances is that her enthusiasm vastly outweighs her work ethic, and it’s here where the film should delve into the insufferable, because it has every reason to. Frances is an over-sharer, an under-achiever, she overstays her welcome, drinks too much, talks too much, she deflects any opportunity — even small, helpful ones — out of some misplaced stubborn pride, but Gerwig sells the performance magnificently, and in places, bravely. (She cinched her first Golden Globe nomination for her trouble.) The film retains an euphoric, Bowie-infused apex in spite of, or maybe because of, its leading character.

NOSTALGIA-FEST OR REPRESSED NIGHTMARE? This is one of those times where RETROGRADING’s template is a bit too hard-lined. Nostalgia-fest? Repressed nightmare? Good god. Frances Ha is neither of those things; it’s a perfect moment in cinema, an example of the creative process and the love that went behind it. Frances Ha is a snapshot of a happier time, moved from box to box to box, becoming more precious as the years progress. It’s a film that says the transition from child to adult can be a wonderful thing, even with all the flakiness and eleventh-hour regret that goes with it.

RETROGRADE: 10 out of 10