By Jarrod Jones. David F. Walker can write about superheroes and techno-aliens and basically any fantastic thing you can find between the barriers of a comic book panel. But what he excels at is writing about people. Real people. You. Me. The way we shuffle past each other on the street. How none of us don’t pay any mind to each other on our daily commutes. The people who make up the world. David F. Walker populates this sensational medium of ours with living, breathing human beings. It’s what he’s good at. It’s his gift.

And if he proved anything with Dynamite Comics’ Shaft, one of my picks for the best miniseries of last year, Walker can even turn a legend into a regular human being. And Ernest Tidyman’s John Shaft — with his infamous ability to out-suave, out-punch, and outwit any fool that comes his way — is practically an American folk hero. What sets him apart is that he definitely won’t be martyred like John Henry, nor will he be villainized like John Dillinger. John Shaft doesn’t have a hammer and a cause or a string of knocked-over banks to cement his place in American folklore. He has his strength. His moxie. His determination to see the bad guys lose.

And even though the extreme things he does may be at times beyond our meager understanding, even if the things he does are informed by an anger (or in some cases, a hate) some of us can never know, so long as he remains in David F. Walker’s hands, John Shaft will always, always, remain a person. In Walker’s hands, John Shaft is a man wise beyond even his own reckoning. He sees the world for what it is.

“Life isn’t measured in hours, or days, or weeks, or years. It’s measured in before and after.”

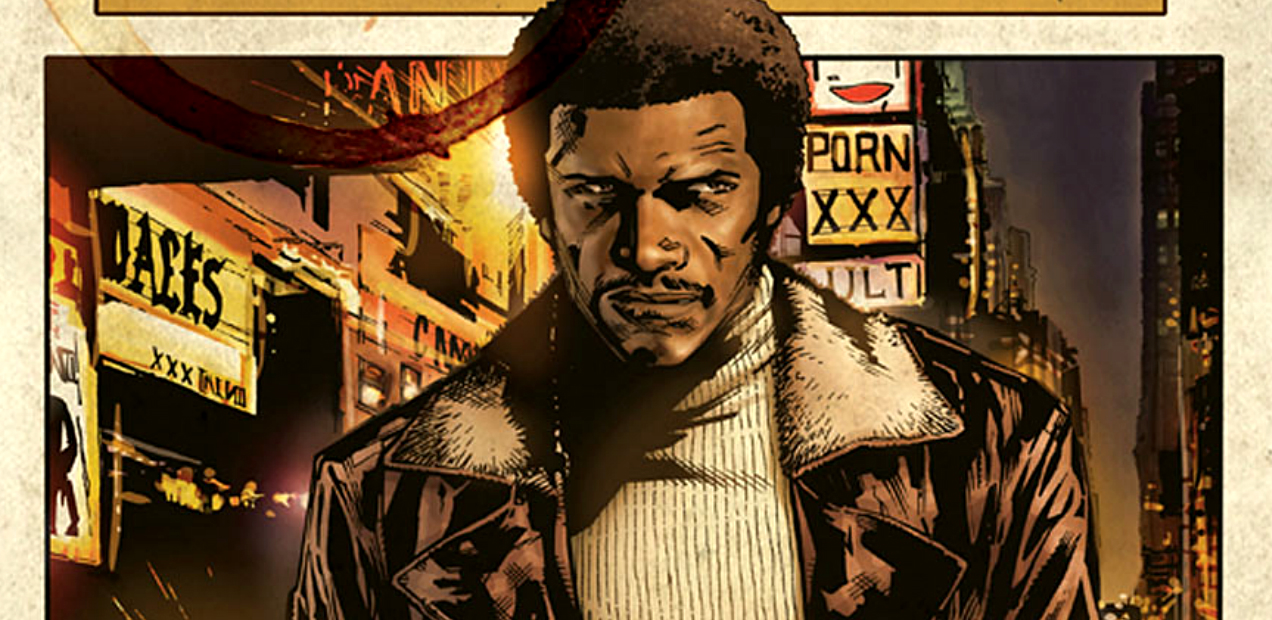

Walker doesn’t seek to deify John Shaft. He makes it perfectly clear that Shaft is no angel, just another broken soul in a city full of broken souls. He doesn’t bother attempting to obscure the private eye’s own personal prejudices, either: admire the man for sending three rapists straight to the Lake of Fire one minute, and then tsk as you watch him sneer and squirm inside a gay bar the next. You can see what the external forces around Shaft do to the man. His posture straightens whenever he feels threatened. His eyebrow cocks when somebody starts to talk some shit. He admires the angular majesty of a newly formed mustache, and then uses to emphasize his expressions to maximum effect. We know this because Shaft: Imitation of Life has an artistic ace in the hole, and his name is Dietrich Smith.

Dietrich Smith’s good in the quiet moments. He aces the likeness of Richard Roundtree in a way we just didn’t see in Walker’s first Shaft miniseries. In Imitation of Life, John Shaft looks just like John Shaft. And Smith doesn’t stop there; while it may feel a touch on-the-nose (subtextually, anyway) that Shaft’s latest charge (a youth named Tito Salazar) would be the spitting image of Sal Mineo, Smith’s renderings remain spot-on; he employs the two actors’ likenesses to further Walker’s story, not distract from it. There’s no lightboxing done here. (A gripe I’ve had with another book recently.) Smith knows what he’s doing, and Shaft is all the better for it.

Once the action starts, however, that’s when the sophistication of Smith’s work begins to deteriorate into a grotesque havoc. And maybe that’s the point, that at the moment where John Shaft turns from an earnest private eye to a vengeful urban warrior all the patience and diligence is removed from Smith’s renderings to emphasize the skirmish. He makes violence look like violence as we know it in life: awkward, ugly, and mostly without a point. That’s what makes a lurid yarn like Imitation of Life such essential reading. It allows us to enjoy the uglier parts of life without ever once taking them for granted. Keep your eyes looking forward, but make damn sure to throw a glance over each shoulder as you continue on your way.

Dynamite/$3.99

Written by David F. Walker.

Art by Dietrich Smith.

Colors by Alex Guimarães.

Letters by David F. Walker.

9 out of 10